Opioid Overdose Deaths in Tennessee

Key Points

- Opioid overdose deaths (ODD) are best understood as three phases: first due to prescription opioid misuse, followed by a rise in heroin use, and currently due to contamination by synthetic opioids such as fentanyl. Each phase has posed unique policy challenges.

- Numerous policies and practices have successfully reduced prescription opioid and heroin ODD, but ODD due to fentanyl and other synthetic opioids continue to rise, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic began.

- Fentanyl test strips, syringe service programs, greater naloxone (Narcan, Kloxxado) availability and other harm reduction approaches have been implemented in recent years with positive results, but synthetic opioids continue to cause deaths due to their extreme potency and widespread availability.

- Expanding access to treatment is crucial to reducing ODD. Such policies include initiating medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) within jails and emergency departments, reducing the behavioral health workforce pay gap, and expanding health insurance access.

- Additional harm reduction and prevention policies may have an even greater impact on reducing ODD.

Opioid Overdose Deaths (ODD): Three Phases

In the late 1990s, due to misleading and aggressive marketing by Purdue Pharma and other drug manufacturers that novel opioids such as OxyContin were non-addictive, physicians across the country began dramatically overprescribing opioids. This caused widespread prescription opioid misuse among patients, wherein people were improperly sharing prescriptions. In the early 2010s, over 60% of people with a known history of opioid prescription misuse reported obtaining their first dose from a friend or family member either for free or for a price. By 2012, opioids had overtaken alcohol as the primary substance of dependence among those receiving treatment funded by the Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services, while drug ODD increased 220% from 1999.

Healthcare providers, insurers, and policymakers began reacting to what had then become an epidemic of opioid misuse. In 2014, Tennessee launched the Prescription to Success Act, a statewide strategic plan developed by the Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services and other agencies to build on existing efforts to combat the epidemic. Key elements of this plan included establishing a Good Samaritan law, revising the Tennessee Intractable Pain Treatment Act and Tennessee Code to reform prescribing guidelines and better regulation of pain management clinics, restricting direct-to-consumer advertising for pain medication, implementing new guidelines for acute care and emergency room prescribing, improving the Tennessee Controlled Substance Monitoring Database (CSMD), and many other efforts that had a demonstrable and significant impact on the rate of prescription opioid misuse and ODD.

Unfortunately, as the supply of prescription opioids became more restricted, many people began turning to illicit sources such as heroin. Even as ODD due to prescription opioids declined, deaths due to heroin overdose began spiking, especially as synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, which is up to 100 times stronger than morphine, entered the market. In 2019, three out of every four heroin ODD involved fentanyl. Fentanyl has quickly become the number one cause of opioid ODD, and is now involved in over 50% of all drug ODD.

It is important to keep in mind that the majority of all opioid ODD involve multiple drugs, known as polydrug overdose. This means people are pairing opioids with a benzodiazepine or a muscle relaxer, further enhancing the depressant effects, or with a stimulant like methamphetamine or cocaine in order to counteract the opioid’s depressant effect with the stimulant’s energy boost. Polydrug use is often intentional. Even as deaths due to fentanyl and other opioids continue to climb, the rate of polydrug overdose has remained stable since 2015, meaning that the overdose epidemic cannot be viewed as a problem exclusive to opioids.

| The Danger of Fentanyl Many people unknowingly ingest fentanyl for several reasons. Despite being exponentially stronger than heroin, fentanyl is about 18.5 times cheaper (heroin costs about $65,000 per kilogram and fentanyl about $3,500 per kilogram). Because of this, dealers can maximize their profits by lacing fentanyl into other substances, even mixing it with flour or baking soda. Dealers also lace fentanyl into other illicit drugs, including methamphetamine. All illicit drugs carry the risk of fentanyl contamination.A particularly nefarious product is the fake prescription pill: dealers use illegal pill presses to manufacture a fentanyl-laced pill that resembles OxyContin or another prescription, such as counterfeit Xanax. People that buy these pills on the street think they know what drug and dose they are about to ingest. However, due to the presence of fentanyl, they unintentionally overdose.Importantly, some people intentionally seek out fentanyl because their baseline tolerance has grown so high that synthetic opioids are the only way to feel the euphoric effects that make the drugs addictive in the first place. Despite their high tolerance, even these individuals risk death because there is no way to know for sure the potency of any drug bought on the street. |

Responses to a Changing Problem

The first phase of the opioid epidemic was met with policies and programs that had a strong impact on reducing ODD involving prescriptions, but the heroin and fentanyl phases introduced new challenges that have been met with new solutions. In 2018, Tennessee released a multi-faceted plan known as TN Together, which builds on the Prescription to Success Act. Among prevention strategies such as changing TennCare coverage to limit opioid prescriptions, $25 million was appointed to treatment programs, including within correctional facilities.

There have been several harm reduction efforts as well. In addition to expanding access to the opioid antagonist naloxone and providing civil protection to those who administer it, Tennessee legalized syringe service programs (SSPs) in 2018. SSPs are significant distributors of naloxone, and importantly, SSP participants are five times more likely to enter long term recovery treatment.

The Pandemic Effect

Despite these monumental efforts, the coronavirus pandemic contributed to a dramatic, unprecedented, and persistent spike in ODD. Between February 2020 and April 2021, Tennessee saw a 60% increase in ODD. Widening our scope, we see a 101.2% increase in ODD between January 2019 and January 2022, with an overall quintupling since the start of the epidemic in 1999. There are more people dying of overdose than ever before in the state’s history, and it is clear that the pandemic was a significant contributor to this acceleration.

In response to the pandemic, Executive Orders and Special Session legislation increased telehealth permissions, which significantly expanded access to medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD), contributing to a marked increase in patients seeking recovery services in Tennessee. These permissions were made permanent in 2022. Tennessee also passed Public Chapter 771 and Public Chapter 761 in the summer of 2020, authorizing nurse practitioners and physician assistants to prescribe the MOUD buprenorphine in various contexts. Early the next year, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services removed the requirement for prescribers to undertake specific training courses in order to gain buprenorphine privileges.

| Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Research shows that medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) dramatically reduce the risk of death. However, MOUD still remain underutilized in residential treatment programs. However, MOUD acceptance is growing due to the significant increase in treatment retention and completion, overwhelming reduction in mortality, suicidality, and crime.Naltrexone is an opioid antagonist, meaning it blocks opioids from binding to receptors, making it impossible to get high. It does not prevent withdrawal, however.Methadone is an opioid agonist, meaning it is itself an opioid, but much less potent than heroin or fentanyl. Its primary purpose is to allow the patient and their provider to taper down the patient’s daily opioid intake, so that they can control withdrawal symptoms and enter long term recovery. Additionally, methadone has been strongly associated with a reduction in illicit drug use such as heroin.Buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist, meaning it binds to opioid receptors and blocks any further opioid doses from having an effect while also preventing withdrawal symptoms. Additionally, Buprenorphine is less likely to be misused due to these receptor blockers. Buprenorphine is known to have a mortality benefit of at least 50%, meaning that more than half of patients taking it would have otherwise died by overdose. |

Additionally, the CDC announced in April 2021 that federal funds may be allocated to Fentanyl Test Strips (FTS), and in March 2022, the Tennessee General Assembly passed Public Chapter 764, excluding FTS from being considered drug paraphernalia. As the name suggests, the test strips indicate if there is a presence of fentanyl in any substance tested. Studies have shown that FTS are effective in reducing risk of OD by changing drug use habits and using safely through avenues such as SSPs.

Remaining Challenges

While access to treatment has been significantly expanded (especially via telehealth) and TennCare’s coverage of services has increased, there are still several barriers to access for many Tennesseans.

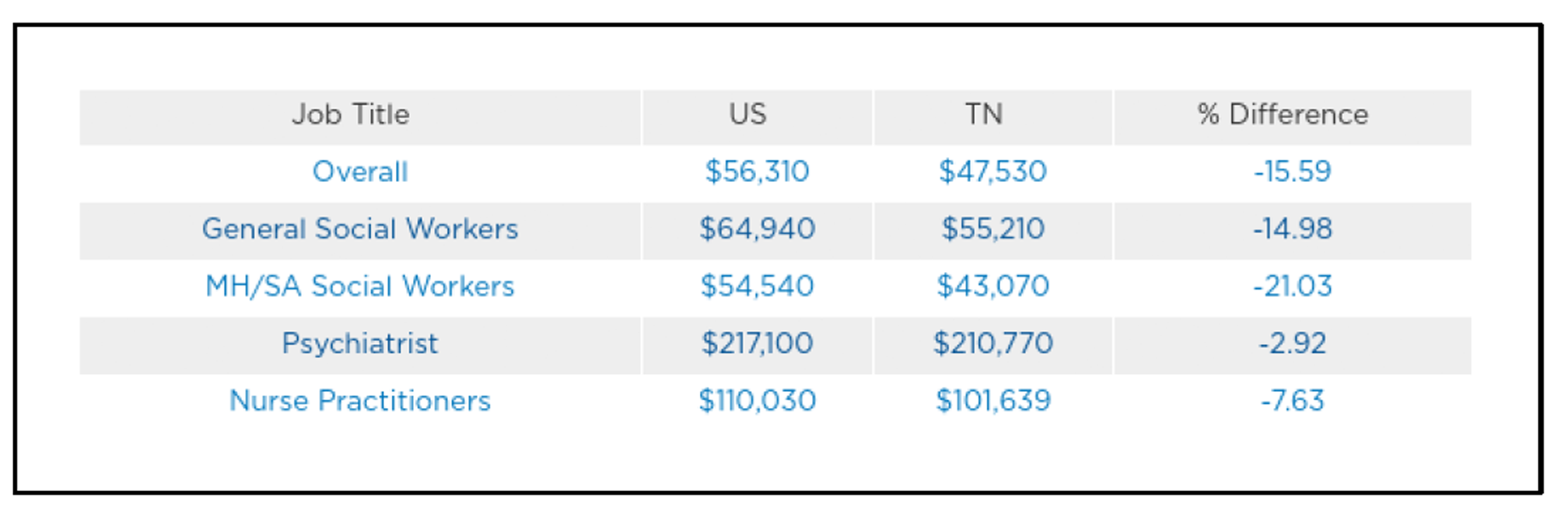

Despite changes at the federal and state level to increase the number of providers capable of prescribing buprenorphine, there were only 1,007 such providers in 2020 in Tennessee. About half of these had a patient cap of 30, and 26 counties lacked such a provider altogether. Additionally, it is anticipated that Tennessee’s behavioral health workforce shortages will worsen. By 2030, Tennessee is expected to have a gap of 780 psychiatrists, 830 substance use counselors, 890 psychologists, and 1,270 mental health counselors. Overall, only 13.2% of Tennessee’s psychiatric needs are being met. A significant contributor to this is a gap in reimbursement rates. On average, Tennessee pays its behavioral health workforce over 15% less than the US average. Social workers specializing in mental health and substance use are particularly impacted, receiving an average of about 21% less pay than their peers in other states.

A major cause of the pay gap is the large number of uninsured Tennesseans, which are overrepresented in the substance use population. Over 11% of Tennesseans – nearly 800,000 people – do not have health insurance of any kind. Even with telehealth permissions and increased TennCare coverage, treatment can be prohibitively expensive for the population at greatest risk for fatal overdose. Uninsured patients must pay for services with cash, and as MOUD treatment can cost almost $5,000 per patient per year, many patients simply cannot afford services even when they are available. Because opioid use is associated with a significant decline in workforce participation, and a person’s likelihood of passing a drug screen dramatically affects employment opportunities, it is clear that the population at greatest need for public insurance is the population at greatest risk of opioid death: the uninsured.

| Knox County Overdose Fatality Review The Overdose Fatality Review (OFR) is a new interagency task force whose purpose is to “take a deep dive into the lives of individuals who have fatally overdosed to identify trends and missed opportunities that occurred during their life.” This involves reviewing medical records, data from the criminal justice system, toxicology reports and many other sources in order to build a comprehensive picture of the trends that are associated with fatal overdoses so that prevention efforts can be better informed and targeted.Dr. Maranda Williams, the current director of the Knox County OFR, hopes to make the biggest impact on encounters with emergency departments and incarceration facilities, as these are major points of contact between people with substance use disorder and potential access to resources. A notable finding is that overdose deaths typically occur in people that lack health insurance, and similarly lack legal prescriptions.The Knox County OFR began in 2021, and there are hopes to launch teams in Davidson, Rutherford and Hamilton counties as well. While they are having an impact, Dr. Williams informed SMART that they have been limited in some ways. For example, they are not allowed to interview families of subjects. |

Policy Options

Access: MOUD in Correctional Facilities and Emergency Departments

Due to over 80% of all Tennessee crimes relating to drugs and people with substance use disorder being overrepresented in the incarcerated population, the criminal justice system represents an important treatment access point. If a person with an opioid use disorder is incarcerated, it will not take long before opioid withdrawals begin. Similarly, such a person is at markedly heightened risk of overdose death upon community re-entry due to a natural reduction in tolerance. If, however, MOUD treatment is continued or initiated during incarceration, there is a significant reduction in ODD upon re-entry. Such a program has been launched in Jefferson County, Tennessee. For more information, please see our policy brief on continuity of care for incarcerated populations.

Similarly, the predominant model for addiction treatment in the context of emergency departments (EDs) is known as Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT), wherein the treating provider – more often than not following the reversal of a potentially fatal overdose – discusses substance use disorder with the patient and gives them a referral list for nearby programs. While the SBIRT model does have some efficacy, studies show that initiating MOUD treatment in the ED is even more effective, with an increased chance of patients utilizing long-term recovery services, decreased drug use, and decreased use of inpatient services. The American College of Emergency Physicians now recommends that providers initiate MOUD treatment in the ED.

Harm Reduction: Supervised Injection Sites

By increasing the availability of naloxone and legalizing syringe service programs, Tennessee has already begun to embrace harm reduction policies in an effort to reduce ODD. However, fentanyl is so lethal and so available that people are still dying in the “largest numbers we’ve ever seen,” despite the monumental steps taken thus far. Supervised injection facilities (SIF), also known as overdose prevention centers, are a type of harm reduction program not unlike syringe service programs (SSPs). Whereas SSPs provide a place for people who use drugs to obtain clean hypodermic needles and naloxone, as well as connections to long term recovery services, SIFs also provide a space for people to inject drugs under the supervision of a clinician trained in naloxone administration. SIFs have been associated with a marked decrease in overdose mortality compared to the surrounding areas (35% decrease versus 9%), a significant reduction in infectious disease transmission (such as HIV) as well as overall drug use, and increased access to healthcare and social services. In November 2021, two SIF opened in New York City and averted 59 overdose deaths in the first three weeks of operation. The first legal SIF in the United States was opened in Rhode Island earlier that year. Though the Department of Justice prevented the opening of a facility in Philadelphia in 2019, the DOJ has not interfered with either the Rhode Island or New York facilities.

Policy Brief Authors:

Jeremy Kourvelas, MPH, SMART Initiative, UT Institute for Public Service

Erin Gwydir, Student, UT Knoxville, Department of Political Science

Jennifer Tourville, DNP, Executive Director, UT Institute for Public Service

Karen Pershing, MPH, Executive Director, Metro Drug Coalition

Secondary Authors:

SMART Policy Network Steering Committee Members