On May 21, the New York Times published an article titled “Has Fentanyl Peaked?” The premise is that the “opioid crisis…may finally be turning around” based on the fact that preliminary data from the CDC shows that drug overdose deaths slightly declined in 2023, now down to 107,543 estimated deaths (or about the equivalent of a plane crash every single week).

Practically declaring victory, even going so far as to describe fentanyl as a “fad,” the author goes on to attribute the reduction in deaths as a “natural” result of drug trends entering a market, spreading, and fading away “at least for some time.” He then also lays the laurels at the feet of federal, state and local efforts to increase the distribution of “Narcan, also known as naloxone” as well as increasing access to addiction treatment. These are definitely effective policies that have saved lives, but the idea that the overdose crisis is beginning to end is factually wrong.

It is certainly true that drug trends change over time, and opioids are no different. Prescription opioids shifted to heroin when those prescriptions became hard to get. Seeing an easy profit to be made, the cartels started pumping synthetic fentanyl into the market and the drug’s potency, combined with its disturbingly low cost, led to a surge in overdose fatalities that became a leading cause of death for all Americans aged 18-45, and contributed to the first reduction in the overall life expectancy for the United States since 1920.

The author of “Has Fentanyl Peaked?”, however, is ready to say that the “opioid epidemic appears to have entered the final phase” based on the data from last year. As previously mentioned, the CDC estimates that 107,543 people died of a drug overdose in 2023, down from the all-time high of 113,103, which was the estimated number of people who died in the 12-month period ending in…May of 2023. Any reduction in overdose deaths is certainly a win, but it is far too early to say that the data show a clear and sustained reduction in fatalities. Besides, the reduction is far from close to being able to talk about this crisis entering “the final phase.” After all, when President Trump declared the opioid crisis to be a national emergency in October 2017, the estimated number of overdose deaths that year was 71,646.

Plus, we never know what is just beyond the horizon that could change the whole equation. For example, there was a sustained, steady decline in deaths from 2018 through the end of 2019, but then the COVID-19 pandemic hit, leading to widespread isolation and a national mental health emergency, and overdose deaths skyrocketed. In Tennessee, the overdose fatalities nearly doubled from 2019-2021.

The author of “Has Fentanyl Peaked?” states that “The Covid pandemic is over, taking with it the chaos and isolation that led to more overdoses.” The COVID-19 pandemic is certainly over, but declaring that isolation is no longer a problem in America is incorrect. While the pandemic exacerbated the problem, it is merely a footnote in the Surgeon General’s 2023 report titled “Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation,” which calls for a widespread “movement to mend the social fabric of our nation.” Not exactly a sign that the problem is over.

The author then proclaims that “The drug users most likely to die have already done so.” Setting aside the dismissive and cold nature of this statement, it ignores the fact that every one of these deaths was preventable in the first place, and it says nothing of the risk present for those who are still alive. Fentanyl is still very much ubiquitous in the drug supply, and deaths are still well beyond the emergency level.

Fentanyl is far from the only problem

The author makes the confident (and uncited) assertion that “More people have rejected opioid use.” This ignores the important fact that fentanyl is not the only drug killing people.

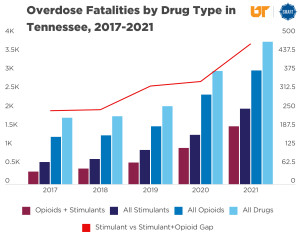

The author makes a passing reference to what he calls the “fads” of “crack, meth and synthetic marijuana,” acknowledging that for meth in particular “a comeback is underway,” as if he were talking about bell-bottom jeans. This is an underestimation of the severity of stimulant use in the current era, which has been described as the “fourth wave” of the overdose crisis.

No, methamphetamine and cocaine are not just making a comeback. The rate of use of these stimulants – and dangerous use, such as injecting, in particular – has nearly tripled, and on top of that, the rate of deaths involving just a stimulant is increasing faster than the rate of deaths involving both stimulants and opioids like fentanyl. In other words: the number of people dying from just stimulant use is increasing faster than the number of people dying from taking stimulants and fentanyl combined. Fentanyl is far from the only problem.

Chart from the SMART Initiative’s “What is the Risk of “Captagon” and Other Pill-Pressed Stimulants in Tennessee?”

There is also no mention in the article about xylazine, the veterinary tranquilizer that does not respond to naloxone and has been increasingly found in counterfeit pills in a manner very similar to the fentanyl trade. There’s also no mention of designer benzodiazepines like bromazolam or other novel psychoactive substances. And there’s not a single word about the increasingly unexpected combinations of drugs showing up in the market that are a cocktail of unknown substances to the user. With this in mind, the author’s assertion that “the remaining users have learned how to use fentanyl more safely” seems naïve. Harm reduction – including fentanyl test strips and other drug checking equipment, syringe service programs, and more – is definitely a valuable policy framework that has certainly saved lives and connected people to recovery services. But there is no truly safe way to use fentanyl, or any illicit drug, which could be a combination of substances that cannot be detected by the user and may have unexpected side effects, and importantly, may not even respond to naloxone.

The article at least acknowledges that more work is to be done. The problem is a mountain and we are only able to move one stone at a time. This crisis, which should be thought of as overdoses, not just a crisis defined exclusively by opioids, is related to our national epidemic of loneliness and isolation, economic changes and poverty, long-standing histories of generational trauma, child abuse and neglect, and so many other old and painful issues. Reducing everything down to just one drug and taking the first sign of decline as victory is short-sighted, and vastly underestimates the severity of the problem.

– Jeremy C. Kourvelas, MPH